A frequent trope in many teacher-lounges is about how much better the students used to be in the “good old days”. While I suspect that many of these claims are based on selective memories, there is one such conversation that has stayed with me. A colleague said to me that it used to be that when he spoke about the obligation for married women to cover their hair, there would be protests and arguments from the female students. Now, he said, they just write it down in their notes and spit it out on the test. Interestingly, he was suggesting that he missed the days when students cared enough to argue. While I would disagree with his claim that students don’t care, I think he brings up an interesting point.

There are often discussions about what students should know by the time they graduate high school. I would like to suggest that we also think about what students think by the time they graduate. If I had to pick one thing that I would like my students (and children, for that matter) to possess by the time they are 18, it is a sense that Judaism and Torah matter enough to engage in the religious struggle that is an inherent part of engaging in Torah. In a thoughtful essay, Akiva Weisinger discusses the implications of Yaakov’s wrestling match with the malach, and the subsequent change of his name to Yisrael. He suggests that the struggle with God and his Torah is inherent to the Jewish experience. I sometimes wonder whether we are doing enough to ensure that our children and students will care enough to engage and struggle with our collective beliefs, teachings and ideas.

How do we get there? I think there are things that parents and educators can do to make it more likely that our children and students will take the idea embodied in the name Yisrael seriously.

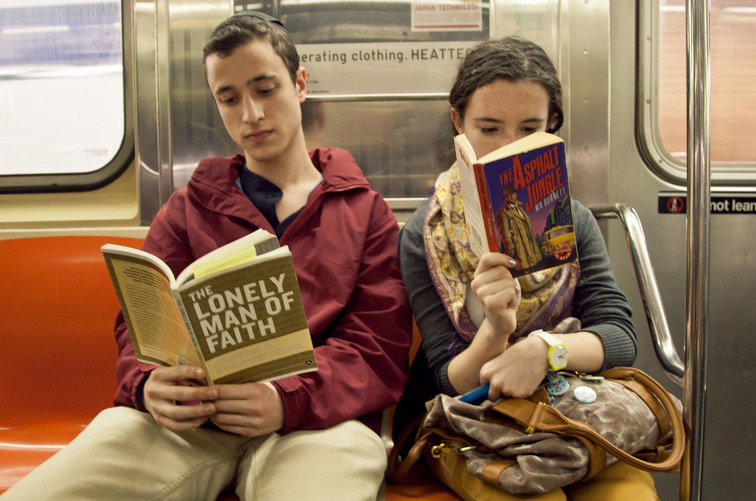

To begin with, we need to model the struggle. Whether it is at the Shabbos table or in discussions in the classroom, teenagers benefit from seeing that we practice what we preach. If we share our struggles, as well as talk of how we are dealing with them, it is more likely they will see this behavior as normative and important. We all need downtime. As with everything we do, our children see what we do when we have a few minutes to spare. To the degree that we spend time seriously engaging with sefarim and books that show that we are invested in the struggle, we can hope that our children will do so as well.

Educationally, it is important that we choose texts and subjects that are not merely about knowing facts. When we teach halacha, one of the reasons why it is wrong to teach it as merely a set of rules, is that it fails to show how the mitzvohs themselves have the potential to challenge us to think. Taamei HaMitzvohs should be a part of any discussion of halacha. Additionally, as I have mentioned before, we do a disservice to our students when we only teach the halachic parts of the gemara. It is in the aggadah that Chazal expresses some of their most profound ideas. By seriously engaging in the study of aggadah, we not only expose our students to essential ideas, but also allow them to engage with these beliefs and concepts. Finally, we as educators have to be up to the task. Any question that our students ask should be dealt with seriously, and that puts the onus on us. We need to study both religious and secular texts that we might not have learned in yeshiva or school. While it is obvious that we can not have the answers to all questions, it is imperative that we do as much as we can to show that we have seriously engaged in areas like philosophy, history and science and their implication for Judaism.

Whether it is in college, yeshiva, seminary or later in life, our children and students will likely have moments where they need to decide if Judaism is important enough to be part of forming their worldview. While we can not make this choice for them, the actions we take as parents and/or educators will play a significant role in their decision.

Post by Pesach Sommer.