The other day, I commented to my wife how glad I was that the seforim on our shelves are being used so frequently. While this was perhaps, in some small measure, an attempt to justify my frustrating habit of not returning sefarim to the shelf and putting sefarim back in a fairly messy way, there was much more behind my comment. To me, it is sad to walk into a house and see from the sefarim that they are positioned in a way that suggests that they are hardly ever used. Essentially, I was saying that no one would ever make that mistake by looking at our shelves. Thinking about it a little more, that’s only half true. It depends upon which of our shelves one looks.

We have about 6 bookcases packed with sefarim in our living room, with three on one wall, and the other three on the adjoining wall. Along one wall, are the sefarim that deal with Tanach and machshava/philosophy. On the other shelves, are sefarim that deal with gemara and halacha. Of course, being that these sefarim are mine, it’s not quite that neatly divided, but I digress. The first set of shelves look as if they have been hit by a tornado. Sets are somewhat broken up, sefarim lay horizontally on top of other sefarim, and everything looks used. By contrast, the Shas and halacha shelves are, if not collecting dust, way too ordered and neat. It’s hard for me not to think about what this means.

For a long time, my learning interests tended to be talmudic and halachic, as were the shiurim I gave. I loved tracing a topic from its talmudic roots through modern day posekim. I would often pick up a SHU’T (Shailos and Teshuvos) to see how a modern posek dealt with a particular subject. All of that has changed. While I continue to be fully observant and enjoy hearing halacha shiurim when the chance comes up, that is not the area that draws my mind and heart. These days, I am more likely to pick up Rav Kook rather than Rav Moshe, the Moreh rather than the Mishnah Torah, and the Tzidkas HaTzaddik rather than the Mishnah Berura.

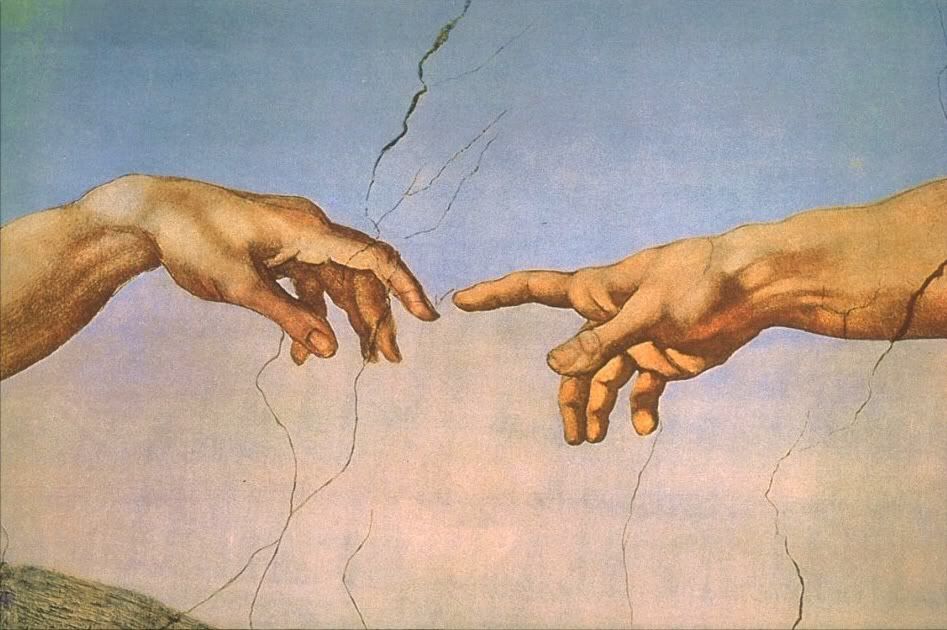

This was brought home to me last night when I posted a comment that contained a few sloppy mistakes about halacha. While it was by no means part of a serious Torah post, I couldn’t help but realize that I wouldn’t have made that same mistake five years ago. Whereas a number of friends took the opportunity to push me to return to a more balanced approach, I’m not yet ready to find the middle ground. For now I simply recognize that I traded one pole for its opposite. I know the middle exists, and I will one day find it, perhaps by looking at the interplay between the two poles, but for now, I am not yet ready.